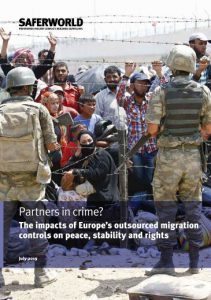

In Partners in crime? The impacts of Europe’s outsourced migration controls on peace, stability and rights, veröffentlicht im Juli 2019, schreiben Ruben Andersson und David Keen für Saferworld über die EU-Politik der Externalisierung von Grenzen und deren Kontrolle. Anhand der EU-Politiken in der Türkei, in Libyen und dem Niger zeigen die Autoren auf, wie sich die EU-Politik sowohl kurzristig auf Migrierende und Flüchtende auswirkt, als auch langfristig auf die Situation in den Herkunftsländern.

Hauptthese der Autoren ist, dass die EU so langfristig Fluchtursachen verstärke.

Die Autoren heben den direkten Einfluss der EU-Abschottung auf die Menschenrechte Migrierender und Flüchtender hervor, die gravierend missachtet werden. Die EU allerdings rühmt sich damit, dass sie die Zahlen der in Europa Ankommenden „effektiv und nachhaltig“ gesenkt habe. Aber ganz im Gegenteil. Andersson und Keen zeigen vielmehr, dass das Outsourcen von Grenzschutz langfristig zu Instabilität in den Ländern führt, in denen die EU aktiv ist und damit im Gegenteil Fluchtursachen sogar befeuert werden. Dass die EU mit (nicht-)staatlichen Akteuren zusammenarbeitet, von denen bekannt ist, dass sie Menschenrechte brutal verletzen, untergräbt ihre eigene Inszenierung als Hüterin der Menschenrechte. Damit verwirkt sie die Möglichkeit, Menschenrechtsverletzungen glaubhaft anzuprangern – schließlich setzt ihre Abschottung die Verletzung von Grundrechten geradezu voraus.

Tatsächlich hat das in und um Europa gewachsene System der Migrationskontrolle heute den Effekt, verschiedene Arten von menschlichem Leid zu tolerieren und sogar zu erleichtern, um die Migration abzuschrecken, während gleichzeitig die Verantwortung an Dritte ausgelagert und die damit verbundene Gewalt verschleiert wird – zum Beispiel durch humanitäre oder rechtliche Rhetorik.

Andersson und Keen problematisieren im Zuge dessen auch das von der EU propagierte Verständnis von Migration als Unsicherheitsfaktor. Indem die EU Migration nur als Sicherheitsangelegenheit darstelle, die ein abschottendes Bordermanagment erfordere, legitimiere sie ihr brutales Vorgehen. Die beiden Autoren fordern eine Policy-Verschiebung von Grenzschutz zum Schutz von Menschen und deren Rechten.

Migration into Europe has fallen since 2015, when more than one million people attempted maritime crossings. This decrease follows the EU and European governments’ narrow focus on reducing migrant numbers and the externalisation of border security measures and migration controls to its borderlands and wider neighbourhood. On numbers alone, the policy could be considered ‘effective’. However, the policy ‘outsources’ migration controls to a range of state and non-state third parties who are largely unaccountable and often employ coercive methods including arrest, detention and forced returns to contain and control migrants. This puts people at risk in both migrant and host communities and fuels a damaging and ultimately self-defeating system that rewards abusive behaviour and fuels instability on Europe’s borders. […]

In the short term, there is a direct human cost in lives and livelihoods – the percentage of people who died or who are missing at sea in the central Mediterranean shot up from 2.6 per cent in 2017 to about 10 per cent in the first few months of 2019. Abuse, extortion and inhumane conditions for migrants have been widely documented in EU-supported ‘buffer’ states. […]

Migration control is often presented as a response to criminality, but EU policy is actually fuelling predatory and criminal behaviour by generating perverse incentives in ‘partner’ countries. […]

‘Partner’ states get political legitimacy and impunity for abusive behaviour and also receive economic dividends, including for their security apparatuses. The costs of this approach include: sidelining deeper efforts to address instability; directly or indirectly undermining stability, rights and livelihoods; and making migration routes more dangerous, undermining regional mobility and increasing desperation. Allowing widespread fatalities and abuses to occur on Europe’s doorstep also fundamentally undermines the reputation and values of EU institutions. Likewise, overlooking forced returns in contradiction of United Nations (UN) conventions undermines the rules-based international order, diminishing Europe’s leverage in pushing for human rights to be respected around the world.

The border security approach persists because it frames a complex issue in politically advantageous terms – as a response to fear and to an existential threat. It can claim ‘success’ by citing reductions in migrant numbers to the EU while ignoring the wider costs of the policy. It enrols a significant number of largely unaccountable third parties who can gain from or manipulate the system. It distributes costs and risks in a politically advantageous way. […]

But it is possible that migration initiatives driven by the EU and member states are now benefiting from many of the dubious advantages surrounding the projection of power and the generation of suffering via ‘proxy forces’ (whether formal military actors or various semi-legitimate or illicit armed groups in ‘partner countries’). This is particularly alarming because, by enabling such crackdowns, the EU and many of its member states are signalling that they tolerate repressive politics or some form of human rights abuses from governments in ‘partner’ countries. […]

In fact, the system of migration control that has grown in and around Europe is today having the effect of tolerating, and even facilitating, various kinds of human suffering as part of an attempt to deter migration while simultaneously outsourcing responsibility to third parties and obscuring the violence that this inevitably involves – for instance via humanitarian or legal rhetoric. […]

Besides the chaos and fear stirred among the public in European countries by hard security measures, there are many risks in ‘buffer regions’ of the current security approach. First, there is the danger of reinforcing authoritarianism, internal repression and human rights abuses (whether directed at migrants or non-migrants). Second, there is the risk of instability or outright military conflict arising from the support and legitimacy accorded – directly or indirectly – to a range of dubious security actors, from state forces to paramilitary groups. Where fragile countries are destabilised (as in Niger), there are likely to be many dangerous knock-on effects. […]

Meanwhile, framing mobility as a ‘crime’ tends to position governments as ‘the good guys’ and disguises the important role that authorities (whether outside or inside the EU) are playing in actively fuelling violence, alongside various forms of irregular or semi-legitimate armed groups or forces. […]State actors (even highly abusive ones) are likely to be legitimised and praised as saving people from smugglers, even though they may be involved in a variety of criminal activities themselves (including, of course, the facilitation of smuggling itself). Meanwhile, undermining economic activity associated with migration may deepen poverty and create associated risks of violence (as in Niger).

All of these dynamics are destabilising. Chaotic arrival scenes, fuelled by ‘double gaming’ and repression, may act to destabilise border communities, including in Europe (and, by extension, may destabilise national political environments). Containment and ‘hostile environment’ strategies may fuel social tensions, as many migrants and refugees live in defined spaces with highly constrained opportunities. […]

From West Africa to the Maghreb, and from the Horn of Africa to Syria’s neighbourhood, the list of countries caught up in the perverse incentives encouraged by the EU’s securitised approach to migration is long and troubling.

A new discourse and normative vision could take hold if it does not distinguish between protecting citizens and foreigners in a zero-sum game, and instead emphasises the need to guarantee protection and rights for all. This would mean recognising that guaranteeing safe movement for refugees and vulnerable people will reduce chaotic and abusive situations at borders, and that improving the rights for all in both European and non-European countries – particularly social and economic rights – can help stem the fears that the now chronic ‘crisis’ of migration has become indelibly associated with in European politics.